According to the Myers-Briggs Personality Test I am an INTJ

(Introverted, iNtuitive, Thinking, and Judging). Out of the 16 personality types the test

comes up with, INTJ is one of the rarest, with only 1-4% of the population

exhibiting these characteristics.

Positively known as the “Scientist,” INTJs typically choose careers in

the sciences and engineering, but can be found in all areas of academia where a

combination of intelligence and incisiveness are required. INTJs rise to managerial positions, but they

are not the typical idea of what a “leader” should be.

Because of their introversion, INTJs tend to come off as quiet and

reserved, preferring interactions with a few close friends over a large group

of people. Combined with an affinity for

intuition, INTJs constantly gather observations on the world and making

associations with it, drawing connections which may not be obvious to others. Quick to understand new ideas, INTJs are more

focused on applying concepts than understanding the intricate meaning

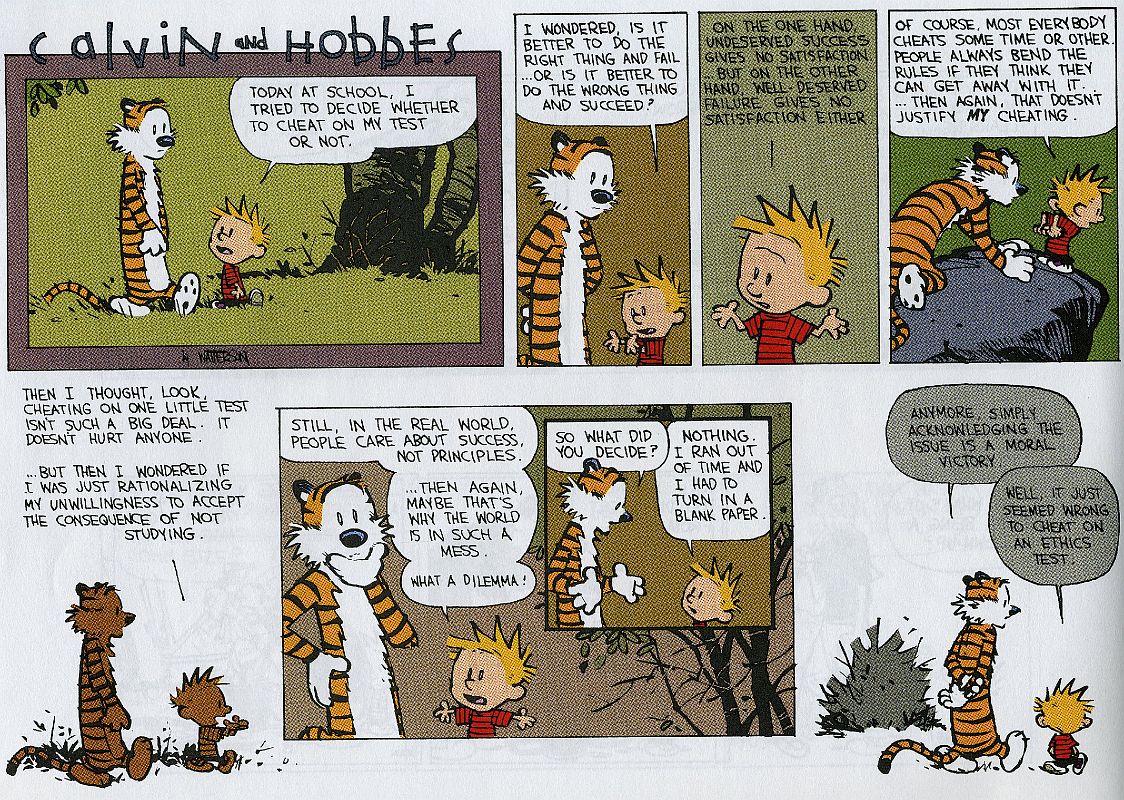

behind something. INTJs are noted for

their preference of thinking over feeling.

Valuing the common good over personal problems, logic is more heavily

employed during decision making than social considerations. These decisions are made early, since INTJs as

judging also plan their activities meticulously and thrive on control through

predictability.

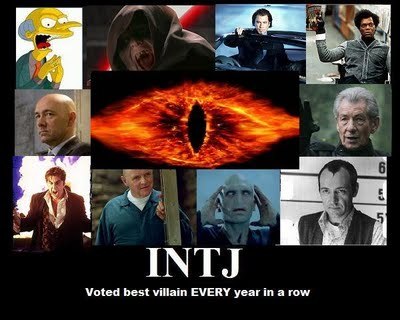

So who are these INTJs?

Well…

True, a less flattering term often applied to this

personality type is “Mastermind.”

Rational Masterminds, primarily associated with INTJs, are reluctant but

capable leaders who are very sure of themselves. Direct and to the point, pragmatic almost to

a fault, and willing to do whatever it takes to see that a goal is

accomplished, Masterminds have commonly been associated as diabolical

manipulators. While this may be true of

certain fictional villains who exhibit the traits of an Introverted iNtuitive

Thinking Judging type, there are other leaders in history who have been

identified as INTJs. They include:

- Hannibal - Carthaginian general considered to be one of the greatest military commanders in history

- Augustus Caesar - first emperor of the Roman Empire

- Thomas Jefferson - third president of the United States and author of the Declaration of Independence

- James Polk - eleventh president of the United States and instigator of the Mexican-American War

- Chester Arthur - twenty-first president of the United States and creator of the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act

- Susan B Anthony - prominent American suffragette

- Woodrow Wilson - twenty-eighth president of the United States and delegate at the Paris Peace Conference

- Calvin Coolidge - thirtieth president of the United States during the Roaring Twenties

- John F Kennedy - thirty-fifth president of the United States during the Cuban Missile Crisis

- Donald Rumsfeld - Secretary of Defense under Gerald Ford

- Michael Dukakis - 1988 Democratic presidential candidate

- Rudy Guiliani - former mayor of New York City

- Colin Powell - former four-star general and Secretary of State under George W Bush

- Hillary Clinton - Secretary of State under Barack Obama

- Michelle Obama - First Lady and advocate for poverty awareness, nutrition, and healthy eating

As shown by this diverse list, INTJs can be found in all

facets of society and have accomplished great things, from crossing the Alps on

elephants to founding a nation.

When dealing with individuals in an organization it is

important to realize that different personality types will react to situations

in differing manners. Managers who are INTJs

will be less likely to empathize and respond with sympathy to their colleagues’

problems. They will also work better in

small groups and with like-minded people.

Jobs requiring creativity will be more pleasing to an INTJ worker, as

well as those that require analytical thinking.

When placed in a stressful situation, INTJs will focus on minute

details, a strategy which is not coherent with their usual big-picture

thinking. Many people have a hard time

understanding a person exhibiting INTJ characteristics. They are seen as aloof, rigid, set in their

ways, and are not prone to praising someone’s success. This is not necessarily true, but understanding

that a person does not respond in the same way as yourself is important when

looking into how an organization successfully functions.

Myers-Briggs Personality Tests are easy, self-administered

tests which can help a person to explore the unique aspects of their personality. Leaders are representative of all sixteen

personality types and each trait has the potential to be used effectively in a

managerial capacity. By understanding

each type it will be easier for people to work together in a group.

Bibliography

"INTJ Profile." INTJ Profile."INTj Uncovered." INTj Uncovered.

"More About Personality Type." More About Personality Type.

"Portrait of an INTJ - Introverted INtuitive Thinking Judging(Introverted Intuition with Extraverted Thinking)." Portrait of an INTJ.