Case in point: in 1995 the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum made plans to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. The exhibit was called The Crossroads: The End of World War II, the Atomic Bomb and the Cold War and would center around the fuselage of the Enola Gay, the Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber that dropped Little Boy on Hiroshima. Immediately, protesters from the American Legion and the Air Force Association stirred up controversy, accusing the Smithsonian of placing too much emphasis on the destruction of the Japanese city and not taking into account the WWII veterans and how beneficial the decision was. Feeling it was an attempt to disparage those that were involved in the bombings, numerous veteran groups rallied against the exhibit. With enough negative attention focused on the exhibit, the Smithsonian decided to cancel the proposed project. The controversy also prompted the Air and Space Museum Director, Martin Harwit, to resign.

1) The dilemma of time: short-term versus long-term interventions cause time blindness; this results in seeing something as an answer for today and not what will be affected in the long-term as a result.

2) The dilemma of interest: personal interest versus group interest causes relational blindness; seeing the cause-and-effect as only pertaining to one’s organization is flawed as everything is connected to the whole.

3) The dilemma of scope: a limited, clear scope versus a wide, more complete and complex scope causes spatial blindness; while organizations may see parts of a system they are unable or unwilling to piece it together as a whole.

In order for organizations to flourish, they need to be able to ask—and expect ongoing debate—the question of “Whatever I do, is it good for us, is it good for others, and is it good for the greater good?” If careful thought is given to the answers of this question, then an important ethical question can be discussed in a meaningful way. Integration of the three kinds of ethics—egoistic ethics (consideration for the self is both the first and last priority), mutualistic ethics (giving as much as is being received), and altruistic ethics (giving and expecting nothing in return)—will result in a thought-provoking discussion resulting in a decision not hastily made towards a delicate question.

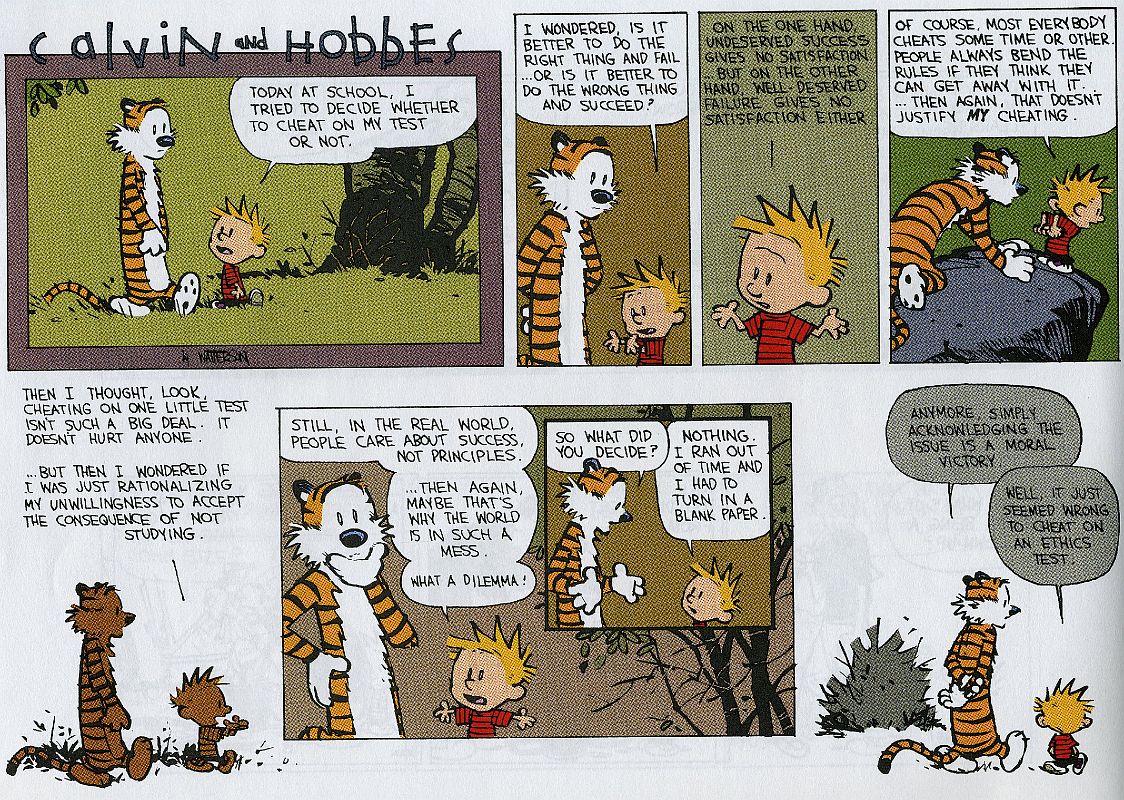

While the topic of ethics in the workplace is generally limited to an individual’s behavior (ie, stealing, lying, abuse, etc.) there can, and often are, ethical dilemmas faced by the organization as a whole. Properly identifying these instances and opening a thoughtful dialogue is the first step and, regardless of whether or not a decision is reached, the mere thought of attention being paid to such an unpopular topic is a victory in and of itself. As to the question of solving the ethical problem, there are ways in which organizations can weigh the options and reach a reasonable conclusion. For the most part this consists of answering the question of who will benefit from a proposed solution and how it will affect people not directly associated with the process. If enough organizations can put the subject of ethics into their business practices then perhaps we can avoid the fate that Calvin has pinpointed.

Bibliography

2) The dilemma of interest: personal interest versus group interest causes relational blindness; seeing the cause-and-effect as only pertaining to one’s organization is flawed as everything is connected to the whole.

3) The dilemma of scope: a limited, clear scope versus a wide, more complete and complex scope causes spatial blindness; while organizations may see parts of a system they are unable or unwilling to piece it together as a whole.

In order for organizations to flourish, they need to be able to ask—and expect ongoing debate—the question of “Whatever I do, is it good for us, is it good for others, and is it good for the greater good?” If careful thought is given to the answers of this question, then an important ethical question can be discussed in a meaningful way. Integration of the three kinds of ethics—egoistic ethics (consideration for the self is both the first and last priority), mutualistic ethics (giving as much as is being received), and altruistic ethics (giving and expecting nothing in return)—will result in a thought-provoking discussion resulting in a decision not hastily made towards a delicate question.

De Graff, Ann, and Joost Levy. "Business as Usual?: Ethics in the Fast-Changing and Complex World of Organizations." Transactional Analysis Journal 41.2 (2011): 123-28.

No comments:

Post a Comment