How can someone measure happiness? Can it even be measured? What can we use to measure happiness? Over hundreds of centuries philosophers have attempted to define the concept of “happiness” and to also locate its source. Aristotle came close when he revealed that “happiness is the purpose of life, and living in accordance with one’s virtues is how to achieve happiness.”

Aristotle seemed to be on the right track, for a group of psychologists in the United States and Switzerland conducted a survey asking participants to rank characteristics linked to life satisfaction. The US sample was comprised of over 12,000 people who completed the survey on http://www.authentichappiness.com between September 2002 and December 2005. The Swiss group, while smaller (less than 500), participated by handing in written surveys that were arbitrarily given to random people. The findings indicate that both groups ranked love, hope, curiosity, and zest as their top responses. Not all the rankings were universal, however, as the graph below indicates:

This discrepancy in how Americans and the Swiss view aspects of happiness is indicative of how the characteristics of different cultures plays a key role in how individuals will try to attain happiness. Americans operate in a highly individualistic environment, which proves to be different from the more collectively-minded countries like Hungary and Switzerland. If working with people from a different cultural background from you, it is important to keep these thoughts in mind, otherwise the goals and attitudes of those involved will be greatly at odds.

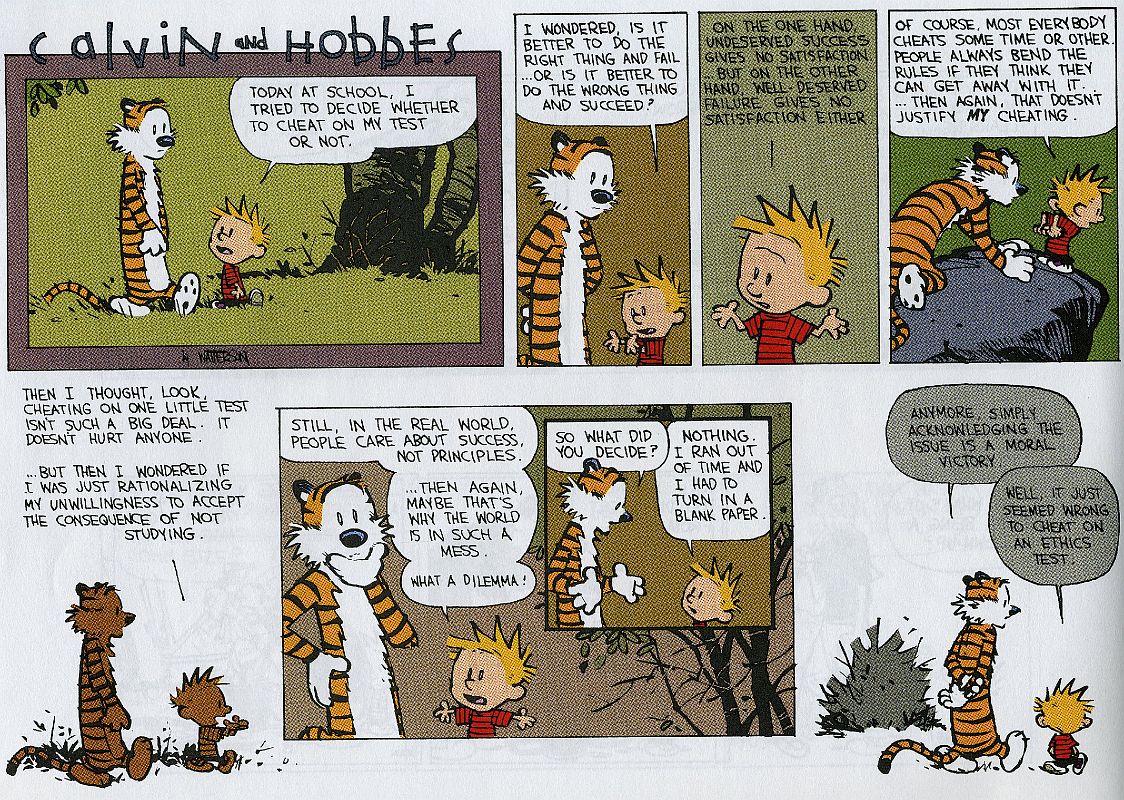

It was uncovered that there are some universalities in the pursuit of happiness, however. Those that go to Marquette are already knowledgeable about the Jesuit tradition of serving others. What is interesting is that the traits that are associated with a meaningful life scored highest on both the tests given in the United States as well as in Switzerland. The next highest group to be scored were the traits characterized as engaging. Pleasurable traits were the last to be ranked, distinctly at odds with the hedonistic lifestyle that is so heavily advertised in today’s society.

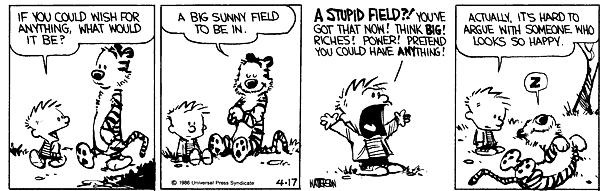

But can happiness really be measured? The stats given to support these findings cannot be presumed to represent everyone in the two countries. The participants were all volunteers with an average age of correspondent well into their adult years and females overwhelmingly were represented. So what is fulfilling for someone of 40 or 50 might not be wholly representative of what I find to be a source of happiness. For me, I experience happiness in a number of different ways: napping in the sun, reading a book for pleasure alone, singing in the car (poorly), telling someone a historical anecdote I find to be amusing, watching childhood cartoons with friends, or making macramé owls. While I would not call these hedonistic pursuits per se, they do emerge as a result of the maximization of pleasure and, selfish person that I am, do not result in a meaningful life. Even if my macramé owls do bring me immeasurable joy.

Even in that vein, when I am at my happiest I do not expect others to illicit that much pleasure from what I am doing. For example, while I may get a kick out of telling the story of William Fitzwilliam to my flatmates, they may not be as interested in it as I am. And they are certainly not going to go around telling historic facts to their friends. So my idea of happiness is not representative of all 21 year old college students, just as the results of the findings do not indicate the goals I find to be most compatible with attaining happiness.

What is important for businesses to uncover—and why the findings of the surveys are so important—is whether the goals of an organization match up with their employees’ ideas of happiness. Job satisfaction is imperative for a business to run smoothly and if someone does not see the business fulfilling their needs or making them happy then they will not perform to the best of their abilities. For this reason, non-profit organizations have the advantage since they—more often times than for-profit companies—are providing jobs that perform meaningful tasks. An employee working for Teach for America, for example, will undoubtedly feel much better about their job than a worker for a big oil company.

By aligning values of a company to appeal to the motivations of the workers, organizations can succeed in creating a work environment for people to thrive in since their needs are being met. When employees feel they are truly making a difference then they will remain happy in their jobs and perform with enthusiasm, enhancing their organizational commitment. They will not fall prey to continuance or normative commitments but instead feel a desire to remain at their jobs since they genuinely want to be there. It will also benefit the company to keep their employees happy, as dissatisfied workers report more psychological and medical problems than their satisfied counterparts. Values, goals, and happiness attributes must remain in sync for an organization to function well.

Bibliography

Bibliography

Nelson, Debra L., and James C. Quick. ORGB. Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning, 2011.

Peterson, Christopher, Willibald Ruch, Ursula Beermann, Nansook Park, and Martin E. P. Seligman. "Strengths of Character, Orientations to Happiness, and Life Satisfaction." The Journal of Positive Psychology2.3 (2007): 149-56.